Types of Bike Lanes and Bikeways: Complete Guide to Bicycle Infrastructure

Follow us on

social media!

The main types of bike lanes and bikeways include shared lanes with traffic, sharrows, standard bike lanes, buffered bike lanes, protected cycle tracks, raised bike lanes, and multi-use paths. Each type offers a different level of safety and separation from vehicles.

Bike lanes and bikeways are not all created equal. Some offer little more than paint on the road, while others provide complete separation from vehicle traffic with barriers, curbs, or dedicated paths. For cyclists, the type of bicycle infrastructure has a significant impact on both safety and comfort.

This guide explains the types of bike lanes, bikeways, and other bicycle infrastructure from the most dangerous conditions, such as roads with no shoulder, to the safest options, including protected cycle tracks and bike-only paths. Along the way, we’ll examine how each facility operates, its advantages and disadvantages, and the research findings on crash reduction and increased ridership.

Table Of Contents

Statistics: The Critical Need for Better Bicycle Infrastructure in the U.S.

Bicycle infrastructure design has a measurable impact on rider safety. National crash data from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) highlight how proper bikeway design saves lives and reduces severe injuries:

- 1,105 bicyclist fatalities in 2022: According to NHTSA, cyclist deaths rose 13% from 2021, underscoring the urgent need for safer roadway designs.

- According to FHWA, Adding bike lanes to roads without them can reduce bicycle crashes by up to 49%

- On two-lane urban roads, bike lanes can lower overall crash rates by 30%.

- The most common posted speed limit in fatal cyclist crashes is 45 mph, highlighting the danger of high-speed road designs.

These numbers underscore why the bicycle lane debate is about preventing serious injuries and deaths through better design.

Why Bike Lanes, Bikeways, and Infrastructure Matter

Bikeways are not just painted lines on a road; they are critical infrastructure that directly affects the safety and comfort of cyclists. Each type offers a different level of protection (and risk), so knowing the options matters.

The Safety Impact of Bike Lanes

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), most fatal and serious bicycle crashes happen at non-intersection locations, and nearly one-third occur when a motorist overtakes a cyclist.

These crashes are especially dangerous because of the speed and size differences between vehicles and bicycles. Fear of this type of collision is also one of the main reasons many people feel unsafe riding on roads without bike lanes or other dedicated facilities.

Bike lanes and separated bikeways reduce conflicts by giving cyclists dedicated space; this is a core principle of FHWA’s Safe System Approach:

- Converting painted or buffered bike lanes into separated bike lanes with flexible posts can reduce bicycle, vehicle crashes by up to 53%.

- Adding bike lanes to roads without them can reduce bicycle crashes by up to 49% and lower total crashes by 30% on certain two-lane urban roads.

These improvements align with the Safe System Approach, which emphasizes designing roadways that account for human vulnerability and separating different users whenever possible.

The data reinforces what many cyclists already know from experience: the dangers of cycling on the road are significantly reduced with proper infrastructure.

Protected Bikeways Increase Cycling Participation

The type of bikeway not only determines safety, but it also influences whether people feel confident enough to ride. A cyclist riding on a rural highway with no shoulder faces very different risks than one riding in a separated facility, and that difference impacts whether people choose to cycle at all.

The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) notes that protected bike lanes and well-designed bikeways significantly increase ridership by making cycling feel safer and more accessible to all ages and skill levels, not just experienced riders.

PeopleForBikes finds that connected, high-comfort bike networks drive the biggest ridership gains. In City Ratings, cities that invest in protected, low-stress bikeways score higher on ridership, safety, and access, encouraging more everyday trips by bike.

Best Biking Cities in the U.S. 2025: PeopleForBikes Releases New Rankings explores how these top-performing cities are leading the way with infrastructure that makes cycling both safer and more practical for everyone.

Bikeway Class System (Overview)

To make bicycle facilities easier to understand, planners often group them into four main classes. This bikeway classification system is widely used in California and referenced nationally by transportation agencies and advocates. Each class represents a different level of safety and separation from motor vehicles.

Class I: Shared-Use Path (Off-Street, Separated)

- Completely separated from roadways

- Used by bicycles, pedestrians, joggers, and scooters

- Example: multi-use trails and greenway paths

Class II: Bike Lane (On-Street, Painted)

- Striped lanes marked on the roadway

- Provide dedicated space for cyclists, but no physical separation

- Example: conventional bike lane next to vehicle traffic lanes

Class III: Bike Route (Shared Road with Sharrows and Signage)

- Cyclists share the lane with vehicles

- Indicated by signage and/or painted "sharrow" symbols

- Example: neighborhood bike routes or streets without dedicated lanes

Class IV: Separated Bikeway (Protected Cycle Track)

- On-street bikeway with physical barriers such as bollards, curbs, planters, or parked cars

- Can be one-way or two-way

- Example: protected cycle tracks in major U.S. cities

Bikeway Protection Levels: Most Dangerous to Safest

| Bikeway type | Protection level | Key safety takeaways | Common risks / limits | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Shoulder (Shared Lane with Traffic) | None | No designated space; high exposure to overtaking traffic, especially at higher speeds | Driver passing at speed; limited operating space | Use full lane where needed per local law/signing |

| Road Shoulder Only | Very Low | Some lateral separation if paved shoulder is usable | Debris, variable width; encroachment by vehicles; not a designated bikeway | Shoulder quality varies widely by corridor |

| Sharrows / Class III | Very Low | Indicates bicyclists may use the travel lane; helps positioning/awareness | No physical separation; often misunderstood/misapplied on faster streets | Not a substitute for bike lanes or separation. |

| Standard Bike Lane (Class II) | Low | Dedicated, painted space improves predictability/visibility | Adjacent traffic; close passes; dooring next to parking | Width: ~5 ft typical; 4–6 ft context-dependent (min 4 ft w/o curb & gutter). Rules on motor-vehicle entry/parking vary locally. |

| Buffered Bike Lane | Low–Moderate | Paint buffer (often ~3 ft) adds shy distance from traffic/doors; reduces sideswipes/dooring risk | Still no physical protection; vehicles can cross buffer | Adding posts/curbs/planters converts treatment to a separated lane. |

| Protected Bike Lane / Separated Bikeway (Class IV) | Moderate–High | Physical elements (flex posts/curbs/planters/parking) limit encroachment; crashes can drop up to 53% when converting from painted/flush-buffered lanes with posts | Intersections need careful design to manage turning conflicts | One-way or two-way; part of many Vision Zero programs. |

| Raised Bike Lane | High | Vertical separation (at or near sidewalk height) discourages vehicle intrusion; improves visibility | Higher cost; drainage/ADA details matter; less common than paint treatments | Included in U.S. design guides; growing use in urban contexts. |

| Shared-Use Path (Class I, Multi-Use Trail) | High | Fully off-street; removes motor-vehicle conflicts | Conflicts with pedestrians/scooters; driveway/road crossings still require caution | Posted speeds and operating rules are local, not national |

| Bike-Only Path | Very High | Highest separation from motor vehicles; comfortable for a wide range of riders | Limited availability; right-of-way and network gaps | Similar concept to European cycle highways; U.S. examples are limited |

Types of Bike Lanes and Bike Facilities

This section spans the range from riding in mixed traffic to fully separated paths. Understanding each type helps riders choose safer routes and helps advocates balance safety, cost, and feasibility.

Least Protected Bikeways

These facilities offer little or no separation from cars, which raises crash risk, especially on high-speed or high-volume roads.

Shared Lane with Traffic (No Shoulder)

Cyclists must ride directly in the same lane as motor vehicles.

- Found on rural highways (55–65 mph) and small neighborhood streets

- Extremely dangerous: no physical separation and limited driver awareness

- Often the highest-risk environment for overtaking crashes

- Legal right to full lane use, but requires constant vigilance

Sharrows (Shared Lane Markings – Class III)

Painted bicycle symbols placed in the travel lane.

- Purpose: to remind drivers that cyclists may "take the lane"

- Limitations: provide no physical space, often misunderstood or ignored by motorists

- Best suited for low-speed, low-traffic streets, but often misapplied to busy roads

- Positioning: typically placed outside the door zone but still within the traffic lane

Road with Only a Shoulder

Cyclists ride in an unmarked paved shoulder space rather than a designated bike lane.

- Benefits: slight lateral separation from moving vehicles only for wider shoulders

- Risks include debris, inconsistent width, sudden drop-offs, and lack of legal recognition as a bikeway. Close proximity to traffic.

- Common locations: rural highways and suburban arterials without dedicated cycling facilities

Many riders wonder whether it’s even legal to bike on high-speed roads or state highways. Laws vary by state, but cyclists typically have the right to use most public roads unless explicitly prohibited. Learn more in our article, Can You Ride a Bicycle on the Highway?

Painted Bike Lanes

Painted bike lanes are the first step up from unmarked shoulders or shared lanes. They designate space on the roadway for cyclists using painted striping, but offer no physical protection from vehicles.

Standard Bike Lane (Class II)

Dedicated, painted lane running alongside motor vehicle traffic.

- Typical width: 3–6 feet (minimum 4 ft where there’s no curb/gutter)

- Provides predictable positioning for cyclists and alerts drivers to their presence

- Risks: still adjacent to traffic; subject to close passing; often placed in the "door zone" next to parked cars

- Most common type of bike lane in U.S. cities

- Legal status: vehicles prohibited from driving or parking in marked bike lanes

Riding safely and predictably in standard bike lanes depends on understanding basic bicycle road etiquette. Cyclists should maintain a straight line, avoid sudden movements, and communicate clearly when merging or turning.

Buffered Bike Lane

A standard bike lane with an added painted buffer (usually 2–3 feet wide).

- A painted buffer may be placed between cyclists and moving traffic, or between cyclists and parked cars

- Safety benefit: added buffer space reduces risk of sideswipes and dooring crashes

- Limitations: still no physical protection; motor vehicles can cross into the lane

- Viewed as an interim step toward protected bike lanes

- Design variations: buffers typically use hatched/chevron markings. If flex posts, curbs, or planters are added, the facility functions as a separated bike lane rather than a buffered lane

Protected and Separated Bikeways

Unlike painted lanes, protected and separated bikeways create a physical barrier between cyclists and motor vehicles, providing a safer environment for cyclists. Protected bike lanes significantly reduce overtaking crashes and increase comfort for riders of all ages and abilities.

Protected Bike Lane (Cycle Track / Class IV Bikeway)

Physically separated from traffic using bollards, planters, curbs, or parked cars.

- Can be one-way or two-way

- Safety benefit: proven to reduce bike–vehicle crashes by over 50%

- Limitations: intersections still present conflict risks if not properly designed

- Increasingly common in major U.S. cities as part of Vision Zero initiatives

- Barrier types: flexible posts, concrete planters, parked cars, or raised medians

Raised Bike Lane

Built above street level, typically at sidewalk height or mid-curb.

- Prevents vehicles from entering the bikeway

- Safety benefit: high level of separation and visibility

- Limitations: more expensive to construct; less common in the U.S. compared to Europe

- Often used in urban areas with heavy pedestrian and bicycle volumes

- Design considerations: requires careful attention to drainage and accessibility

Shared-Use Path (Multi-Use Trail – Class I)

Completely off-street and separated from vehicle traffic.

- Designed for multiple users: bicycles, e-bikes, scooters, e-scooters, dog walkers, joggers, families with strollers, and children on bikes

- Lower Speed Limits: Speed limits are typically posted between 15–20 mph to reduce conflicts among users. Riders who travel above 15–20 mph, such as road cyclists or fast e-bike users, often find that riding on the road is safer and more predictable than using shared-use paths

- Safety concerns: because people move at different speeds and in unpredictable ways, collisions and near-misses are common. Passing slower users requires extra caution. In some cases, crashes between cyclists and pedestrians can result in injuries for both parties. Learn more in our article, Cycling Accidents with Pedestrians: Causes, legal Rights, and Prevention.

- Best use case: casual riding, family outings, and recreational cycling, rather than high-speed training or commuting.

Bike-Only Path

Fully separated and restricted to bicycles only.

- Provides the highest level of safety and comfort for riders

- Most often found in regional networks or park systems

- U.S. examples are rare, but this facility type mirrors Dutch-style cycle highways

- Design standards: typically 8-12 feet wide to accommodate passing and two-way traffic

Less Common Bikeway Types & Variations

Beyond the standard classifications, cities often use additional bikeway designs to address unique roadway conditions. These facilities vary in protection, purpose, and effectiveness.

Advisory Bike Lanes

Found on narrow roads where there isn't enough width for dedicated lanes.

- Broken bike lane lines are marked on each side of the road

- Motor vehicles may enter the bike lane when no cyclists are present

- Best suited for low-traffic, low-speed streets in small towns or rural areas

- Legal framework: requires clear signage explaining shared use rules

Climbing Lanes

Provide a dedicated uphill bike lane on steep grades.

- Cyclists ride uphill in the bike lane (slower speeds), while downhill cyclists share a lane with traffic (faster speeds)

- Helps reduce speed differentials between bikes and cars

- Common in hilly or mountainous regions

- Design benefit: addresses the specific challenge of slow-moving cyclists on grades

Bus-Bike Lanes

Shared lanes reserved for buses and bicycles only.

- Found in dense urban areas with limited right-of-way

- Benefit: removes cyclists from mixed traffic while giving buses priority

- Risk: frequent bus stops may cause delays or conflicts for riders

- Usage rules: cyclists must yield to buses but have priority over other vehicles

Cycle Superhighways / Commuter Corridors

Wide, continuous, often long-distance routes connecting suburbs and city centers.

- Built to accommodate high volumes of bicycle commuters at higher speeds

- Examples: networks in Denmark, the Netherlands, and pilot corridors in U.S. cities

- Design features: minimal stops, grade separation, and possible weather protection

- Target users: daily commuters traveling 5+ miles

Neighborhood Greenways / Bicycle Boulevards

Low-traffic residential streets optimized for cycling.

- Traffic calming features: speed bumps, diverters, signage

- Goal: slow down or divert car traffic while prioritizing bikes

- Best suited for local travel and family-friendly routes

- Implementation: often includes bike-friendly signal timing and wayfinding

Shared Streets (Woonerf Concept)

Originating in the Netherlands, a "woonerf" is a shared street where pedestrians, cyclists, and cars mix.

- Vehicle speeds are usually 10–15 mph maximum

- Design relies on traffic calming, raised intersections, and landscaping to slow cars

- Creates a people-focused environment but requires strict speed enforcement

- Legal framework: pedestrians have right-of-way over all vehicles

Intersection & Specialized Bicycle Infrastructure

Busy intersections are some of the most challenging places for cyclists. Turning vehicles, limited visibility, and multiple lanes of traffic create potential conflict points where crashes are more likely to occur if the infrastructure is inadequate.

To improve safety, cities are implementing specialized intersection designs that provide cyclists with increased visibility and safer movement through intersections.

Bicycle Boxes

Bicycle Intersection Boxes are painted areas in front of vehicle stop lines at signalized intersections.

- Allow cyclists to position themselves ahead of cars at red lights for improved visibility and a safer start when the light turns green

- Benefit: helps prevent right-hook collisions and increases driver awareness

- Limitation: provides no physical separation once traffic is in motion

- Usage rules: cyclists enter during red lights; vehicles must stop behind the box

Two-Stage Turn Boxes

Two Stage Bicycle Turn Boxes are marked zones that allow cyclists to make left turns in two phases.

- Riders cross straight, wait in the turn box, then complete the left turn when the signal changes

- Benefit: avoids merging across multiple lanes of traffic

- Limitation: can cause delays if signals are long or confusing

- Design: typically positioned in the far-side crosswalk area

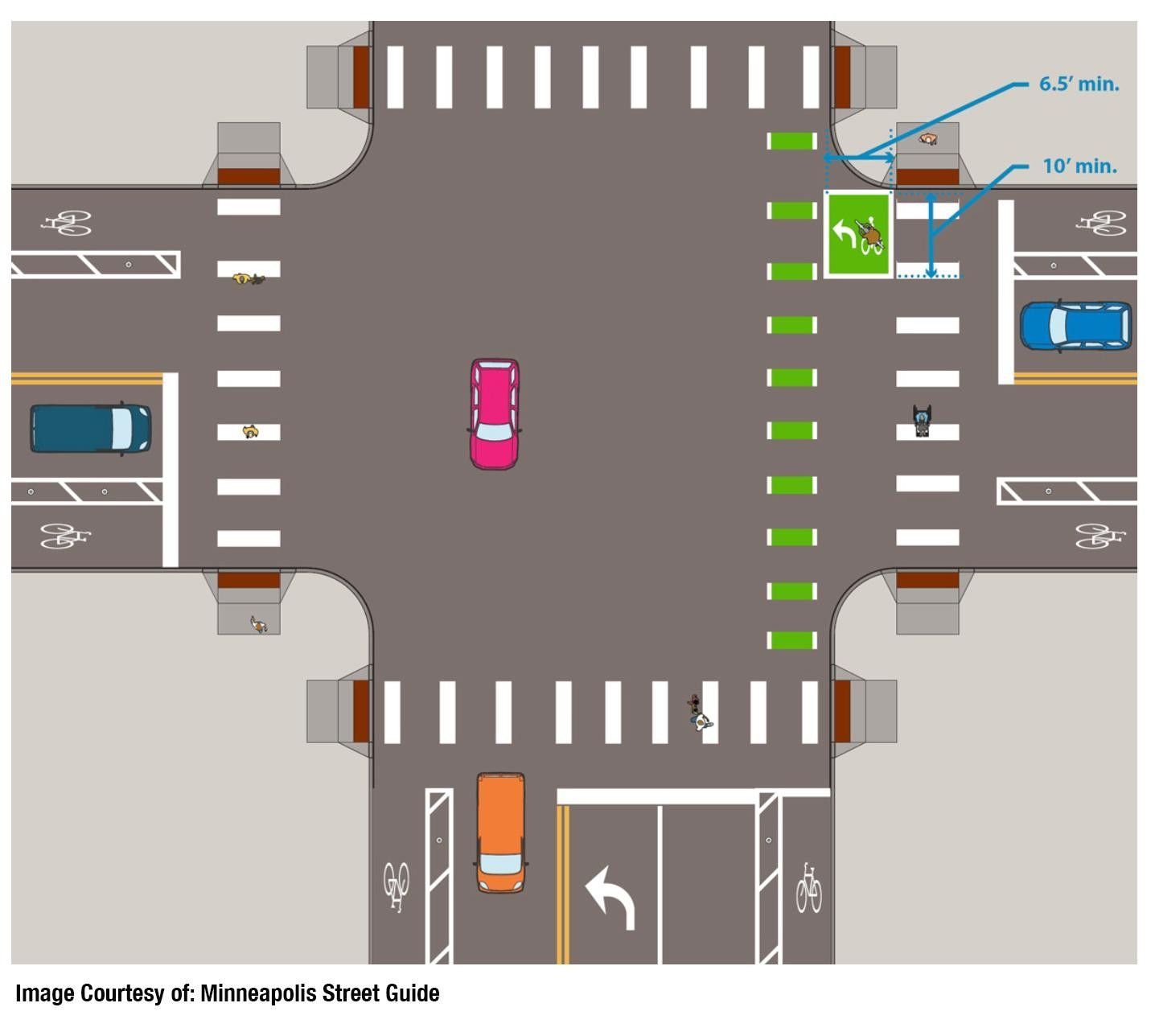

Protected Intersections

Use corner islands, setback crossings, and dedicated bike signals to reduce conflicts.

- Improve visibility between cyclists and drivers, especially during turns

- Benefit: one of the safest intersection treatments available

- Limitation: requires more space and higher construction costs

- Features: corner refuge islands, bent bike lane approaches, and dedicated signal phases

Dedicated Bicycle Signals

Traffic lights specifically for cyclists, often paired with protected intersections or cycle tracks.

- Provide a separate signal phase, reducing conflicts with turning vehicles

- Benefit: improves crossing safety at complex intersections

- Limitation: longer wait times if not well coordinated with other signals

- Types: bike-specific heads, leading bike intervals, and all-way bike phases

Contraflow Bike Lanes

Allow cyclists to travel legally against the flow of one-way vehicle traffic, using striping and signage.

- Benefit: improves connectivity by opening more direct routes

- Limitation: requires strong visual cues so drivers expect opposing bike traffic

- Design elements: "BIKE LANE" pavement markings and "WRONG WAY EXCEPT BIKES" signage

- Safety considerations: enhanced visibility treatments at intersections

High-Visibility Treatments (Green or Colored Lanes)

Bright paint applied through intersections, conflict zones, or across driveways.

- Benefit: increases driver awareness of cyclists' presence

- Limitation: markings fade over time and do not physically prevent encroachment

- Applications: conflict areas, bike lane continuity through intersections

- Maintenance: requires regular repainting to maintain effectiveness

Global and Innovative Bicycle Facilities

Some of the most advanced bicycle infrastructure comes from outside the United States, where cycling is a mainstream mode of transportation. These designs are gradually being tested or adapted in U.S. cities and represent the future of safe, high-capacity bikeways.

Bike Freeways (Grade-Separated Routes)

Long-distance, high-capacity cycling corridors designed for commuting.

- Fully separated from vehicle traffic, often running parallel to highways or rail lines

- Example: Copenhagen's Cykelsuperstier network, which connects suburbs to the city center

- Benefit: enables cyclists to travel quickly and safely without traffic stops

- U.S. pilots: limited examples in Portland, Minneapolis, and Washington D.C.

Protected Roundabouts for Bikes

Dutch-style roundabouts with dedicated bicycle lanes physically separated from vehicle lanes.

- Reduce conflict points between turning cars and through cyclists

- Benefit: proven to lower crash rates compared to traditional roundabouts

- Slowly being piloted in select U.S. cities

- Design features: raised bike lanes, yield markings, and clear sight lines

Rail-Trails

Conversions of abandoned railway corridors into multi-use or bike-only paths.

- Provide long, continuous, and low-grade routes ideal for commuting and recreation

- Example: Katy Trail in Missouri, Minuteman Bikeway in Massachusetts

- Benefits: minimal intersections, consistent grades, and scenic routes

- Network potential: can connect multiple communities over long distances

Bike Escalators and Conveyor Lifts

Mechanical assists that help cyclists travel up steep grades by resting a foot on a moving conveyor.

- Example: Trampe Bicycle Lift in Trondheim, Norway

- Rare but innovative, designed for cities with challenging terrain

- Cost considerations: high installation and maintenance costs limit adoption

- Alternative solutions: electric bike infrastructure and bike-share programs

Implementing Better Bike Lanes and Overcoming Barriers

Designing safer bicycle facilities is only part of the solution; cities also need effective processes for implementation. Upgrading roads with protected bike lanes and safer intersections requires funding, political will, and coordination across multiple agencies.

Progress can be slow, especially in large cities where street space is shared among drivers, transit, cyclists, and parking. One of the most common points of contention is the road diet, a design approach that repurposes vehicle lanes for protected bike lanes or wider sidewalks. While research shows that road diets improve safety for all road users and often have minimal impact on travel times, they face strong opposition from agencies and motorists who fear increased congestion or reduced parking.

Other barriers include public resistance to lane reconfigurations, limited funding, and bureaucratic delays. Jurisdictional overlap between city, county, and state agencies often complicates efforts to create continuous and connected bikeway networks.

Los Angeles offers a clear example. Even after voters approved Measure HLA, which requires bikeways and pedestrian improvements during repaving projects, implementation has been delayed by bureaucracy and political resistance. Our analysis in Measure HLA: One Year Later, Los Angeles Streets Remain Dangerous for Cyclists and Pedestrians highlights how these challenges continue to affect rider and pedestrian safety.

Ultimately, building safer streets takes more than design standards, it requires long-term investment, education, enforcement, and political commitment to ensure protected bikeways become standard practice, not exceptions.

Laws, Rights, and Responsibilities for Bicyclists and Motor Vehicle Drivers

Clear rules of the road help reduce conflicts between cyclists and motorists. While specific laws vary by state, there are consistent principles that define the duties of drivers and the duties of cyclists when using bike lanes, bikeways, and other bicycle infrastructure.

Duties of Motorists

- Safe Passing: Drivers must provide adequate space when overtaking a cyclist to prevent collisions. Most states have a Three-Feet Law, with some states requiring more safe passing distance. .

- Yielding: Motorists must yield to cyclists when crossing or turning across a bike lane.

- No Blocking or Parking: Cars may not block, stop, or park in designated bike lanes except where local law allow. .

- Dooring Laws: Drivers and passengers are required to check for cyclists before opening car doors into the bike lane or roadway.

- Awareness at Intersections: Drivers should watch for cyclists in intersections, especially when making right or left turns.

Duties of Cyclists

- Obey Traffic Laws: Cyclists must follow the same rules as motor vehicles, including stopping at red lights and stop signs.

- Lane Positioning: Riders should use bike lanes where available, but may leave the lane to avoid hazards, or prepare for a turn.

- Signaling: Cyclists must use hand signals to indicate turns and stops when safe to do so.

- Right to the Road: Cyclists may use the full lane when necessary for safety, particularly on narrow roads or where no bike lane is provided.

- Yielding and Courtesy: Cyclists should yield to pedestrians in crosswalks and shared-use paths, and exercise caution when overtaking slower users such as joggers or families.

Safer Streets Start with Better Advocacy: How Bike Legal Helps

At Bike Legal, we’re more than bicycle-accident attorneys, we’re cyclists too. Our team is dedicated exclusively to representing injured cyclists, bringing unmatched experience to every case. From investigating crashes to securing maximum compensation, we fight for cyclists' rights and we win!

Beyond Casework: Safer Streets and Better Bikeways

Our work is more than just legal representation. We advocate for safer streets, stronger bicycle infrastructure, and laws that protect vulnerable road users. Our goal is simple yet ambitious: to eliminate bicycle crashes with motor vehicles by pushing for the changes that save lives.

When Protection Isn’t Enough

Even the best-designed bikeways can’t prevent every crash. When collisions happen, riders need attorneys who understand both bikeway design and the legal complexities of bicycle cases.

What You Can Expect

- Attorneys who understand, care, and know what it takes to win

- Early, thorough investigation and expert FREE consultation

- Focus on full recovery for medical care, future treatment, lost income, property damage, and pain and suffering

If you or a loved one has been injured in a bicycle crash, you deserve representation from people who truly understand cycling.

Contact Bike Legal today for a free consultation. Call 877-BIKE-LEGAL (877-245-3534) or submit a case form to get started.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main types of bike lanes?

The main types of bike lanes and bikeways include shared lanes with traffic, sharrows, standard bike lanes, buffered bike lanes, protected cycle tracks, raised bike lanes, and multi-use paths. Each offers a different level of safety and separation from vehicles, with protected and raised lanes providing the highest protection for cyclists.

Are protected bike lanes safer than standard bike lanes?

Yes. Studies by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) show that protected bike lanes can reduce bicycle–vehicle crashes by up to 53% compared to standard painted lanes. Physical barriers like curbs, bollards, or parked cars create a buffer that limits vehicle encroachment and improves cyclist visibility at intersections.

What do sharrows mean for cyclists?

Sharrows, or shared lane markings, are painted bicycle symbols placed in traffic lanes to indicate that cyclists may use the full lane. They remind drivers to share the road and position cyclists outside the “door zone” of parked cars. However, sharrows do not provide physical separation and are best suited for low-speed, low-traffic streets.

How do bike boxes improve intersection safety?

Bike boxes are painted areas at the front of intersections that let cyclists wait ahead of vehicles at red lights. This improves visibility, prevents right-hook crashes, and allows cyclists to start ahead of traffic when the light turns green. Cities like Portland and New York use bike boxes to reduce conflict points between turning cars and bikes.

What laws govern bike lane use in the U.S.?

Bike lane laws vary by state, but most follow common principles. Cyclists have the same rights and duties as drivers, must generally use bike lanes when safe, and may leave the lane to avoid hazards or make turns. Motorists are prohibited from driving or parking in bike lanes, except when turning or crossing them safely.

Can cyclists ride on sidewalks or multi-use paths?

It depends on local laws. In many cities, cyclists may ride on sidewalks unless prohibited by ordinance, but they must yield to pedestrians and travel at a safe speed. Multi-use paths are open to bicycles, e-bikes, pedestrians, and scooters, but users must follow posted speed limits (often 15–20 mph) and exercise caution when passing.

How can I advocate for better bike lanes in my city?

Start by joining or supporting local cycling advocacy groups that work with city planners to improve infrastructure. Attend public transportation meetings, submit feedback on proposed road projects, and share data on unsafe routes. Citing evidence from PeopleForBikes City Ratings or programs like Measure HLA in Los Angeles can strengthen your case for safer, connected bike networks.